Until his last breath, he refused to compromise on the 72-year-old UN-sanctioned plebiscite, which was never held in Kashmir. And for that, he spent the last decade under house arrest.

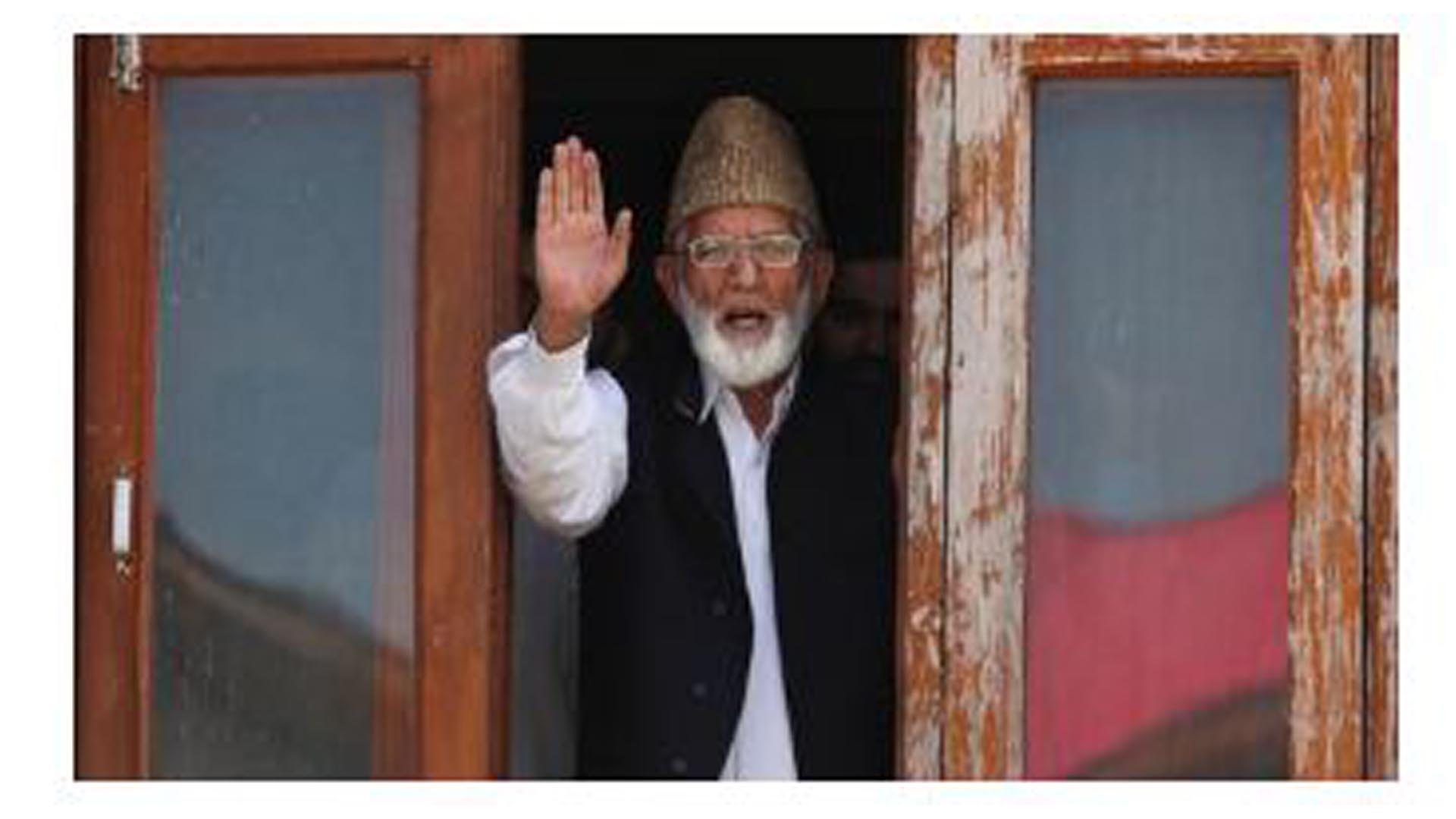

A few years ago, a video went viral in Kashmir in which an old man is seen banging a steel gate with both fists. Through a small, rectangular opening in the gate, he is heard telling a policeman on the other side, in chaste Urdu, ‘open the gate, your democracy is dead, its funeral is underway’.

The old man was Syed Ali Geelani, the most defiant face of the Kashmiri resistance to the Indian rule, who passed away on Wednesday night at his residence in Srinagar, the capital of Indian administered Jammu and Kashmir. He was 91.

For the better part of the past decade, he was never allowed to step out of the gate, not even for specialised treatment in hospitals outside Kashmir, nor for the brief winter stay he would make in the warmer Indian capital for health reasons. He wasn’t allowed to address the media.

Only his family members and a few associates were let inside the residence by a posse of policemen and paramilitary soldiers who stood outside the gate around the clock in a vehicle, or vehicles, depending upon the political atmosphere.

After August 2019, when the Hindu nationalist Indian government scrapped the disputed region’s autonomy, Geelani had virtually become a Twitter account that was operated by a nominated leader who lives in Pakistan.

The account was named Syed Ali Geelani (Official). The last tweet was the announcement of his death and his will to be buried in the Martyrs Graveyard.

Another tweet said the “shameless” local government and police were trying to pressurise the family into burying the leader in the dead of the night at some obscure place.

Hundreds of policemen and paramilitary soldiers were deployed in the area to prevent demonstrations. The police chief of Kashmir announced restrictions would be imposed and the internet would be suspended.

A few days ago, a military drill in northern Kashmir that people said appeared like a routine search operation Indian forces carried out in the region, triggered speculations that the authorities were readying themselves for the aftermath of Geelani’s death.

Why did Geelani scare the Indian state, both in life and death? The answer probably lies in a slogan with which people would greet his presence in both small and mammoth anti-India demonstrations: na jhukney wala, the one who doesn’t bend.

Implicit in the slogan was the indictment that there were many who had succumbed to the machinations of the Indian state in the past and there were others to follow suit.

After all, the once hugely popular Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah, had his grave guarded by policemen lest Kashmiris would defile it for his capitulation before the Indian government.

Whenever Geelani appealed to the people to boycott elections for the local assembly of Indian parliament, reasoning that India showcased them abroad as an acknowledgment of its rule over Kashmir, his critics reminded him of the several elections he had fought under the rubric of the Indian Constitution.

His answer, which had a poetic flourish, was: azmaye huwe ko kya azmana, nothing will come out of trusting the one who has betrayed you.

After all, he had been a lawmaker thrice. His stint in the Indian electoral system had witnessed the gradual disempowerment of a semi-sovereign Jammu and Kashmir, with its own constitution, prime minister and a flag, into a political backwater that India would hold onto with military might, constitutional frauds, installation of puppet regimes and subversion of any fledgling democratic system.

Born into a poor rural family in Sopore, a place famous for apples, Geelani rose in the ranks to become one of the most outspoken members of Jamaat-e-Islami, the largest religio-political organisation in Kashmir.

The largest Kashmiri militant organisation, Hizbul Mujahideen, was widely seen as an armed extension of Jamaat, which was banned by the Indian state last year.

When relentless persecution of its members forced the Jamaat to distance itself from the armed insurgency, Geelani formed his own party, Tehreek-e-Hurriyat. He was also the chief of a faction of an alliance of pro-freedom parties, Hurriyat Conference, until last year when he stepped down citing differences with the constituents.

Right from the eruption of the anti-India insurgency in 1990, Geelani was branded as a ‘hardliner’ for his refusal to engage with the Indian government.

It was not an outright refusal. For him, no engagement was meaningful until the Indian state recognised Kashmir as a disputed region in the spirit of a raft of UN Security Council Resolutions.

The insistence on this point annoyed even his associates in the pro-freedom alliance. He had warned about India’s designs to reduce Kashmir’s Muslim-majority into a powerless minority.

His most often prescribed method of resistance, the strike, would sometimes evoke public ridicule but he would counter his critics by asking them to suggest alternatives.

Jamaat, a proponent of political Islam, had shaped his political outlook. But he aligned with those whose idea of a free Kashmir was completely different from that of his ideological forebears. When an academic recommended to him to separate the accounts of his political and private lives in his multi-volume biography, he wrote:

“When you separate the soul from the body, the burden of the body cannot be tolerated for long. My entire life has revolved around the orbit of Islam and freedom. These two are therefore central to my autobiography too.” He denounced Daesh (Islamic State) as inimical to Kashmiri struggle for right to self-determination.

He remained a votary of Pakistan but, surprisingly, was the only top leader to oppose former Pakistan President Parvez Musharraf’s now famous four-point formula for resolution of Kashmir.

And for all his ‘rigidity’ and religious moorings, the majority of his press releases were addressed to the United Nations.