Zakirova Umida Ismatovna

Abstract

This article explores the phenomenon of English borrowings in the Urdu language, analyzing their historical development, linguistic adaptation, and the impact of English on Urdu’s grammatical and phonetic structure. The study focuses on the processes of assimilation, examining phonological, orthographic, and semantic changes that borrowed words undergo. Special attention is given to pluralization patterns, highlighting instances where English borrowings retain their original plural forms rather than conforming to Urdu grammatical rules. The research also discusses perspectives from linguists on language contact and borrowing theories, including classifications of loanwords and their levels of integration. The paper provides examples of English borrowings that maintain distinct pluralization structures, particularly in institutional and technical terminology. The widespread presence of these elements in contemporary Urdu, especially in media and academia, suggests an ongoing transformation in the language. The study concludes that the continuous influence of English contributes to the enrichment and dynamic evolution of Urdu while also challenging its traditional grammatical framework.

Keywords: loanword assimilation, borrowed words, phonetic and grammatical system, assimilation, exoticism, grammatical markers.

Introduction

The enrichment of a particular language’s vocabulary and its historical development and transformation are influenced by the phenomenon of word borrowing.

The process of word borrowing occurs as a result of language contact, where words, phrases, morphemes, and phonemes from one language are transferred to another. This usually happens through the adoption of words or syntactic expressions from another language. Sounds and word-forming elements assimilate within borrowed words, and as the number of such words increases, they become an integral part of the language.

Borrowed words undergo phonetic and grammatical assimilation according to the system of the receiving language. As a result, they leave a noticeable trace in the language, undergo significant changes, and lose their original characteristics.

The process of word borrowing occurs gradually: it passes through several stages, including words that are completely foreign to the target language, partially and significantly assimilated words that still retain certain characteristics of foreign words, and fully assimilated words, whose foreign origin can only be identified through etymological analysis.

The theoretical foundations of the problem of language interaction were first developed by I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay in 1875 [7, 50]. Later, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, G. Schuchardt introduced the terms language blending and language intersection, the latter borrowed from the field of biology. During this period, the issue of lexical borrowing from one language to another became a central focus of linguistic research. As a result, scholars of the late 19th and early 20th centuries devoted significant attention to defining and refining the terminology used to describe this linguistic phenomenon.

In linguistic studies of this period, the process of lexical borrowing was considered in terms of both calquing and the direct transfer of words, as well as individual morphemes and phonetic elements, from one language to another. As a result, the term lexical borrowing process became widely used in scholarly works as a key descriptor of this phenomenon [11, 89]. Additionally, in the 20th century, linguists proposed the broader term language interaction to describe the various ways in which languages influence each other, encompassing not only lexical borrowing but also phonetic, morphological, and syntactic adaptations [19, 235].Thus, the term lexical borrowing process can be considered ambiguous. On the one hand, it has been understood as the transfer of words from one language to another, occurring in close connection with social life and various cultural phenomena [14, 73]. At the same time, some linguists distinguish lexical borrowing from calquing, treating them as entirely separate processes [10, 178].

On the other hand, the term lexical borrowing process is also used to refer not only to the transfer of a foreign word but to its full integration into the recipient language [2, 7]. As Yu. S. Sorokin noted, “the process of integrating foreign words is a bidirectional process. It is not merely the direct transfer of pre-existing linguistic elements from one language to another, but also their adaptation within the structural and semantic system of the recipient language, their incorporation into its grammatical rules, and their transformation within a new linguistic framework. If we are specifically discussing the lexical borrowing process, then it must be noted that, rather than a mechanical transfer of foreign words into another linguistic system, it is a process of assimilation and adaptation. This process is inherently creative and dynamic, reflecting a high degree of linguistic flexibility and the advanced development of the borrowing language” [14, 202].L. P. Krysin defines the process of lexical borrowing as “the transfer of various linguistic elements from one language to another.” The compilers of the Linguistic Encyclopedic Dictionary adhere to the same perspective [13, 355]. By “various elements,” they refer to units of different linguistic levels, including phonology, morphology, syntax, lexicon, and semantics. Krysin differentiates the borrowing of phonemes, morphemes, lexemes, and other linguistic components [11, 92].

E. Haugen classifies lexical borrowing based on structural characteristics. His classification of borrowed word formation is grounded in the varying degrees of morphological adaptation within the recipient language. He distinguishes true borrowings, where both meaning and phonetic form are adopted from the source language, from hybrid borrowings, which contain both foreign and native linguistic elements. Depending on which component is borrowed, hybrid borrowings are further divided into core borrowings (where the primary component is foreign) and peripheral or marginal borrowings. Moreover, Haugen argues that hybrid borrowings should be regarded as words derived from borrowings rather than borrowings themselves, thus excluding them from the lexical borrowing process proper [17, 344-382].

K. L. Yegorova, refining Haugen’s classification, expands the typology of lexical borrowings by considering their structural properties, semantic features, and the degree of divergence from their foreign prototypes [9, 139]. L. M. Bash’s concept represents both a continuation and an evolution of Haugen’s ideas. According to this framework, the term lexical borrowing process encompasses multiple linguistic phenomena and is therefore divided into direct lexical borrowing and quasi-borrowing (from Latin quasi, meaning “as if” or “seemingly”).

In linguistics, foreign words are traditionally classified into three groups: (1) loanwords, (2) exoticisms, and (3) elements of a foreign language that have entered another language. Loanwords, in turn, are further subdivided into the following categories:

a) Words that structurally correspond to their foreign prototypes, meaning they have been adapted to the phonemic system of the recipient language and may have undergone orthographic changes but do not include any additional structural modifications.

b) Words that have been morphologically adapted using the recipient language’s own morphological mechanisms, meaning that they have undergone structural transformation in accordance with the morphological rules of the recipient language.

c) Words that have undergone partial morphological modification, preserving certain foreign structural elements while integrating into the grammatical system of the recipient language [11, 95].

Thus, loanwords represent a complex and structurally diverse category. However, despite their internal diversity, the words within this group share specific linguistic characteristics that distinguish them from the native lexicon of the recipient language, highlighting the dynamic nature of lexical borrowing and adaptation.

The colonization of India by the British brought significant changes to the lives of its people. In 1835, English began to spread as the official language across the entire country. It became not only the language of education but also that of the press, science and technology, administration, and the judicial system. English became so deeply ingrained in India’s social fabric that even after the country gained independence, it retained its status. Notably, over time, as the negative socio-linguistic perception of English as the language of the colonizers diminished, its influence grew even stronger. Indians increasingly incorporated English loanwords into their everyday speech, and in some cases, entire English phrases became widely usedmany of which have since become integral elements of the modern Hindi lexicon [8; 53].

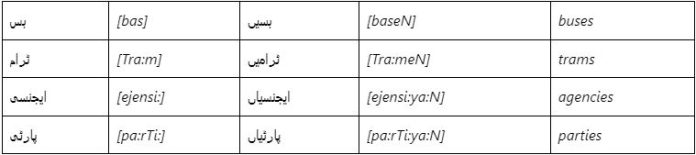

English borrowings in the Urdu language conform to its morphological rules. Although they can be fully integrated into the grammatical structure of Urdu, in some cases, English words retain their original morphological features. For instance, depending on the final letter of borrowed words, they can take plural markers in Urdu. For example, feminine nouns ending in “i” or a consonant in the nominative case receive the suffixes “ya:N” and “eN”:

| بس | [bas] | بسیں | [baseN] | buses |

| ٹرام | [Tra:m] | ٹرامیں | [Tra:meN] | trams |

| ایجنسی | [ejensi:] | ایجنسیاں | [ejensi:ya:N] | agencies |

| پارٹی | [pa:rTi:] | پارٹیاں | [pa:rTi:ya:N] | parties |

This table shows how English loanwords in Urdu follow the language’s morphological rules for pluralization, often adding –eNor –ya:Nas suffixes.

Some phrases have been borrowed from English as whole units, preserving the English plural form. This primarily applies to nomenclature terms, such as the names of organizations, institutions, companies, movements, and similar entities. For example:

| یونائیٹڈ نیشنز | [neishnz] | United Nations | |

| ہیومن رائٹس | [ra:iTs] | HumanRights | |

| پریس کلبز | [klabz] | PressClubs | |

| آرمڈ فورسز | [forsiz] | ArmedForces | |

These phrases retain the English plural form in Urdu despite the language’s own grammatical rules.

| سیکیوریٹی فورسز | [forsiz] | Security forces |

| آل انڈیاانسٹیٹیوٹ آف میڈیکل ساینسز | [sa:ynsiz] | All India Institute of Medical Sciences |

| فیڈریشن آف انڈیا چیمبرز آف کامرس اینڈ انڈسٹریز | [inDasTri:z] | Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry |

The plural forms of the words highlighted above indicate that they are purely English phrases since they are not structured according to Urdu grammar.

However, scientific research shows that nouns borrowed into modern Urdu often retain the English plural suffix “-s,” for example:

| شفا خانہ نے کلینیکل اینیلایزرس درآمد کئے ہیں | [enela:yzers] | The hospital purchased clinical analyzers |

| کانفرینس میں دوسری پارٹیوں کے لیڈرز بھی شامل تھے | [li:Derz] | Leaders of other parties also participated in the conference |

| نئے دو تین ہیلتھ سینٹرز قائم ہوئے | [senTrz] | A few new health centers were established. |

In the words we provided above, there was no necessity to explicitly indicate the plural form, as the plurality is already evident from the verb form. In all three examples, the verb is used in the masculine plural form. In the first sentence, the English word functions as an object, while in the second and third examples, it serves as the subject.

According to the rules of the Urdu language, nouns in oblique cases (except for the direct case) take the plural suffixes “oN” or “yoN” before postpositions. English loanwordsalsofollowtheserules. For example:

| کمپنیوں کے مقابلے میں | Comparedto companies |

In this example, the noun کمپنیappears in the plural form, marked by the suffix وں, in accordance with the postpositional phrase کے مقابلے demonstrating the application of plural morphology in oblique case constructions within Urdu grammar.

| کسٹم نے دو سو بنڈلوں کو روک لیا | The customs officers stopped 200 bundles. |

The sentence کسٹم نے دو سو بنڈلوں کو روک لیاillustrates the use of the plural marker -وں in the oblique case for the noun بنڈل (bundle), appearing before the postposition کو. ThisfollowsthestandardUrdurulewherenounsintheobliquecasetakethe -وںsuffixbeforepostpositions.

| ان پارٹیوں نے بھی مخالفت کی | Thesepartiesalsoopposed. |

Since the transitive verbمخالفت کرنا(to oppose) is used in the past perfect tense, the subject پارٹیوں نے (the parties) is in the ergative case and marked for plurality, following the standard ergative alignment rule in Urdu.

However, the given examples suggest that this rule is occasionally “disregarded,” as English loanwords in such instances retain their plural suffix “-s.” For example:

| ٹیلیفون کالز پر رعایت | Discountontelephonecalls |

| پیداواری یونٹس کو فروغ دینا چاہیے | Production units should be developed |

| جناح ہسپتال میں ڈاکٹرز کی ہڑتال | Doctors’ strike at Jinnah Hospital |

As a result of scientific research, the following conclusions were reached:

Although English loanwords conform to the morphological rules of Urdu,they sometimes retain their original morphological features within the Urdu language.

In contemporary Urdu, the plural forms of widely used English loanwords indicate that they are originally English expressions. These words are not structured according to Urdu grammar, and in many cases, borrowed nouns retain the English plural marker “-s.”

The frequent occurrence of the English plural suffix in the examples above deviates from standard Urdu grammar. However, its widespread use indicates a gradual process of linguistic integration, where such forms are becoming increasingly naturalized in the language.

In conclusion, English has exerted a considerable influence on Urdu, a phenomenon clearly observable in Urdu print media, where linguistic changes are often first documented. These borrowings not only enrich the lexical repertoire of the language but also play a crucial role in shaping its ongoing evolution.

References

- Andronov M. S. English in India: Trends and Development Perspectives – Current Problems of South Asian Language Studies, Moscow, 1987.

- Aristova V. M. On Lexical Borrowings from English into Russian in the 17th–18th Centuries. Moscow, 1978.

- Barannikov P. A. The Linguistic Situation in the Hindi-Speaking Area, Leningrad, 1984.

- Bash L. M. Differentiation of the Term “Borrowing”: Chronological and Etymological Aspects // Bulletin of Moscow University. Ser. 9. Philology. 1989.

- Begizova Kh. B. On the Correlation of English Borrowings and Their Equivalents in Hindi – Current Problems of South Asian Language Studies, Moscow, 1987.

- Begizova Kh. B. On English Borrowings in Hindi – Linguistic Issues, Moscow, 1976.

- Baudouin de Courtenay I. A. Selected Works on General Linguistics. Vol. 1, 2. Moscow, 1963.

- Grishina A. “On the Question of Anglicisms in Hindi: Pronunciation of Anglicisms.” Moscow, 2002.

- Egorova K. L. Types of Linguistic Borrowings (Based on English and Anglo-Americanisms in Modern Russian). DissertationAbstract. Moscow, 1971.

- Efremov L. P. The Nature of Lexical Borrowing and the Main Signs of Borrowed Word Assimilation. DissertationAbstract. Alma-Ata, 1959.

- Krysin L. P. Foreign Words in Modern Russian. Moscow, 1968.

- Larionova E. V. Latest Anglicisms in Modern Russian. DissertationAbstract. Moscow, 1994.

- LinguisticEncyclopedicDictionary. Moscow, 1990.

- Lotte D.S. Issues of Borrowing and Systematization of Foreign Terms and Term Elements. Moscow, 1982.

- Sorokin Yu. S. The Development of the Russian Language’s Lexical Composition. Moscow, 1965.

- Khalmurzaev T.K. The Status of Urdu in Modern India and Trends in Its Development, Tashkent, 1979.

- Haugen E. The Process of Borrowing. In: New in Linguistics. Moscow, 1972. Issue No. 6.

- Shamatov A. N. Essays on the Historical Lexicology of Hindi and Urdu (15th–18th Century). Tashkent, 1990.

- Shcherba L. V. On the Concept of Language Mixing. In: Selected Works on Linguistics and Phonetics. Vol. 1. Leningrad, 1958.

- “QaomiAvaz” Delhi, India.

- “AxbareUrdu,” Islamabad, Pakistan.

Forms of Expression of the Plurality of English Borrowings in the Urdu Language

Zakirova Umida Ismatovna

Senior teacher at the High School of South Asian Languages and Literature

Tashkent State University of Oriental Studies

[email protected] phone: +998909906305