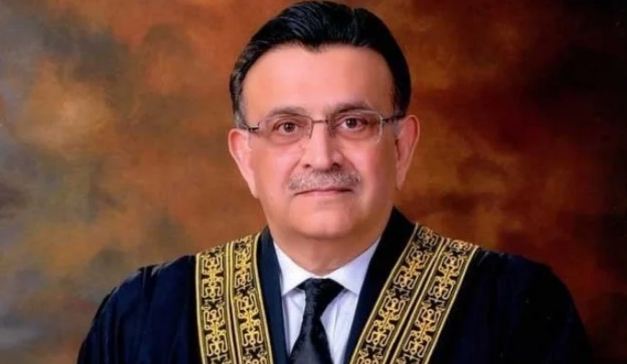

ISLAMABAD, Sept 5: Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) Umar Ata Bandial said Tuesday that a three-member apex court bench hearing the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) Chairman Imran Khan’s petition against the National Accountability (Amendment) Act, 2022 would announce a “short and sweet” verdict soon.

The three-member bench, headed by CJP Bandial, and comprising Justice Mansoor and Justice Ijazul Ahsan, heard Khan’s petition and reserved the judgment on the case, saying that the date of the verdict would be announced later.

“My retirement is near, [we] will give a decision before retirement,” said the CJP, who is set to retire later this month on September 16 and will be replaced by Justice Qazi Faez Issa.

The additional attorney general, who appeared before the bench to represent AGP Mansoor Usman Awan, apologised to the court on behalf of the AGP for skipping the court hearing owing to an important foreign visit.

At the start of the hearing today, the PTI legal counsel, Khawaja Haris presented his final arguments before the bench.

During his arguments, CJP Bandial remarked that the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) had submitted its reasons for the references returned by the accountability following tweaks in the law till May.

“The reasons for the withdrawal of the reference suggest that the law is biased,” he remarked, adding that the people whose references were returned have come on record.

“The first amendment was made to section 23 of the NAB law in May and the second in June. References returned before May are still with NAB. Who will answer these questions on behalf of NAB?” the CJP inquired.

To this, counsel Haris said that many pending cases had been returned after the amendments.

“Be it corruption in state assets, smuggling or illegal transfer of capital, action should be taken,” the CJP said, adding that it was disappointing that these crimes are not clearly defined in the law.

At this, Justice Mansoor asked: “Wouldn’t it be strange that the state should ask why the punishment was reduced in the amendments of the parliament?”

“Can crimes be eliminated by retroactive application of NAB amendments?” the CJP asked, wondering what’s the purpose of applying the law to the past events.

At this Justice Mansoor asked: “Does parliament not have the power to legislate retroactively?

“Can the Supreme Court tell the parliament that you made a law based on cunning and malice?”

He said that if the apex court did not have the authority to amend the legislation of the parliament, then it will have to follow it.

However, Justice Ahsan contended that parliament is not allowed to do everything.

“Parliament cannot eliminate crime by making a law applicable from the past,” he said.

However, Justice Mansoor reiterated his question: “What is the provision of the Constitution preventing Parliament from passing legislation with retrospective effect?”

CJP Bandial added that it could have been said that the law would be applied retrospectively, but resolved cases will not be opened.

” The NAB law should have been clear,” he said, asking, “Can a vague law survive?”

“Adding to the chief justice’s question, can the Supreme Court send laws back to Parliament?” Justice Mansoor asked.

“Parliament is supreme,” Chief Justice Bandial said, adding: “If you ask Parliament to reconsider the laws, what will happen in the meantime?”

“How can the amended law be sent to parliament for reconsideration?” Justice Ahsan asked.

The court itself can look at the law if fundamental rights are affected, Justice Mansoor said; however, he asked it must be explained what fundamental right was affected by the NAB amendments.

“Corruption in public property affects the fundamental right of every citizen of the country,” Justice Ahsan observed.