Staff Reporter

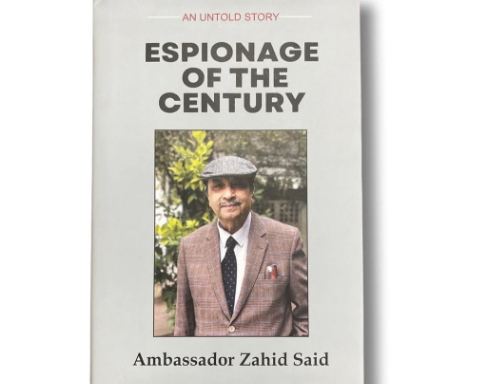

A truthful account of the events that led to Pakistan’s nuclear journey, from scratch to the final accomplishment, ‘Espionage of the Century’ by Ambassador (R) Zahid Said (1938-2020) is now available at bookstalls.

The book published by Sang-e-Meel Publications consists of 281 pages and 17 chapters and keeps the readers hooked as its content fully grasps their attention, moreover, the frank style of the writer has a certain appeal for them.

Without mincing words, Ambassador Zahid Said successfully brings home the message that those at the helm of affairs through their decisions can make or break the living spirit of a nation. The book in fact is a detailed narration by a Pakhtun nationalist who hails from a noble family of Charsadda and received his education from the prestigious educational institutions such as Islamia College Peshawar and Cambridge University.

‘Espionage of the Century’ covers many important turns and twists in the history of Pakistan yet the most riveting chapter is “The Hague, The Netherlands” in which Ambassador Zahid Said gives a vivid account of his meetings with the architect of Pakistan’s Nuclear Programme, Dr AQ Khan and the events that led to his becoming a part of his plan.

Those were the early days of 1974 when both of them happened to be posted in The Netherlands. In the writer’s own words “On 18th May, 1974, Pakistan was suddenly faced with a new challenge: The Smiling Buddha as it was officially called by the Indian government. To dispel international reaction and to avoid sanctions they declared that they had carried out a peaceful nuclear explosion and would not convert their capability to making nuclear bombs.”

Soon after the Indian nuclear test, Chairman of the Pakistan Energy Commission (PAEC) Dr Munir Ahmed addressed Pakistan’s ambassadors, diplomats posted abroad and senior officers of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the ministry’s headquarters in Islamabad. He referred to the emerging nuclear threat from India and told Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was determined to acquire nuclear technology/weapons to meet India’s challenge.

After the meeting, Ambassador Zahid Said returned to the country of his posting (The Netherlands) where he was serving as Counselor. As luck would have it, a young Pakistani scientist Dr Abdul Qadeer Khan was also in the country working on a research project related to the ultra-centrifuge enrichment plant set up by a consortium of three governments—The United Kingdom, Germany and The Netherlands.

Dr AQ Khan approached the writer in mid-December 1974 at The Hague and broached the subject of enriched Uranium technology for Pakistan. This could be risky but the writer decided to give it a chance, and the outcome of their conversation was: India’s claim of peaceful nuclear technology was just a ploy and the Pakistani government under the changing circumstances had the right to develop nuclear capability.

Dr Khan requested Ambassador Zahid to send some documents and other material through diplomatic bag to Islamabad as PAEC Chairman Dr Munir had requested for them. After some reluctance, Zahid Said agreed to receive the huge cache of papers and metal parts of the centrifuge to be shifted to Pakistan unchecked and unnoticed by the local authorities through a diplomatic channel.

In the hair-raising details of the events and challenges that followed the writer brings the material from Dr Khan’s residence to his official building where they lay in the garage for a few days. It was a grave risk and even a minute leakage was sufficient to sabotage the diplomatic ties with The Netherlands. According to the writer, when he informed his boss Agha Shahi, the then Secretary Foreign Affairs about his decision to help Dr Khan [which was in fact a help to his nation and country] he was livid to know how a junior officer of the Pakistani mission could dare act on his own without taking the Foreign Office into confidence. Zahid Said was thus directed to dump the material on some coast of the sea. However, he decided to do the opposite and handed the material to another Pakistani diplomat safely.

Thus the centrifuge’s parts and the huge piles of scientific documents were shifted to Islamabad through many channels. Why did he do so and what made him go against the instructions of the Foreign Secretary? Ambassador Zahid Said himself gives the answer:

“While initially I was preparing to follow the orders, my wife reminded me of my promise to Qadeer Khan to send the material to the concerned authorities in Pakistan. She said I had given my word. It was her words that aroused my conscience enough to disobey Mr Shahi’s instructions and persist in persuading the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to receive the material by sending a high-level courier to take it in several diplomatic bags to Pakistan. It was indeed providential that her earnest remarks had set the ball rolling and had saved the material received from Qadeer Khan from being ‘dumped’ as required by Mr Shahi.” Though published posthumously, the biography was completed by the writer during his lifetime and the credit for both, making the writer pen down his memoirs and then publishing it posthumously goes to his daughter Amina, whom the author calls in the Preface ‘the light of our family.’ “She has been insisting that I write my memoirs ever since I retired from the Foreign Office in October 1999,” writes he.

The book is indeed a must-read as it covers the life of an extraordinary Ambassador and Barrister-at-Law of the International Court of Justice. He shares his early life and career with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs covering his experiences with many notable presidents and prime ministers of Pakistan. Accounts of his diplomatic stints in Senegal, Kuwait, Jordan, Spain and The Netherlands give the readers a feeling as if they were having a visual tour of those countries and meeting people there.